EN | CS | HU

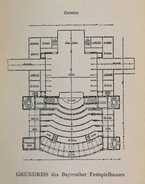

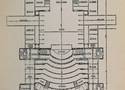

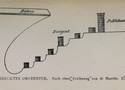

history of the theatresupplementtechnical dataHistoric equipmentFestspielhaus

Otto Brückwald

Festspielhügel 1, | |

| show on the map | http://www.bayreuther-festspiele.de/english/english_156.html |

Important events

(detail)1962 | reconstruction

reconstruction 1962-1973: Lothar Linder

Seating capacity since 1973 = 1925

People

Otto Brückwald |main architect

Lothar Linder |architect

Eberhart Pöhner |architect

H.C. Reissinger |architect

Franz Rank |architect

Gottfried Semper |architect

History

Additional information

No information has yet been entered

Add information