Polski Theatre

ul. 27 Grudnia 8/10 | |

| Prikaži na zemljevidu. | http://www.teatr-polski.pl/ |

Pomembni dogodki

Ljudje

Zgodovina

Although Zofia Ostrowska-Kębłowska claims in her paper concerning the building industry in Poznań that the location of theatres buildings in Poznań, Kraków and Lwów, constructed at that time, is ‘an almost symbolic representation of the position of Poles’ in the areas of partitions, [1] it seems that such changes were visible in most European cities.

The dynamically developing cities more and more often lacked a representative, spacious area that could be used to demarcate a new forum and to construct a theatre there. Basically, such a possibility was created only due to radical urban transformations that we primarily face in new state organisms (such as Belgium, Italy and Hungary), mainly in their capital cities. Characteristically enough, they were patterned on the Paris solution by Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann. [2]

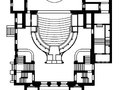

As for the construction of the Polski Theatre in Poznań (1873–1875), it can be believed that the choice of location was determined on the one hand by the question of giving an appropriately high rank to the future building, and on the other hand by the lack of sufficient financial resources. This is why the proposal of Bolesław Potocki, who ceded his garden in Królewska Street in order that the theatre could be located there, was rejected. Eventually the theatre was erected in newly demarcated Berlińska Street. The plot, though located in the centre of the city, was not spacious enough to enable to construct the theatre as a free standing building. Nevertheless, in order to give the building a more representative appearance, it was constructed at the back of the plot with a courtyard in front and a fountain in the centre of it. As a result, the building designed by Stanisław Hebanowski, isolated from street buildings and adjusted in size to the surroundings, looked monumental. As Zofia Ostrowska-Kębłowska put it, the building ‘represented one of the most magnificent types of theatre buildings in the reduced scale and, in addition, it did not bear any resemblance to Berlin school’. [3]

The building was located on the plan of a rectangle with a huge projection in front, basically corresponding to the size of the building. Receding, much lower side parts on both sides of the projection housed corridors and staircases. The central part of the façade was preceded by wide stairs. The dominating element of the façade at the piano nobile became the Italian Renaissance arcade-architrave loggia with richly decorated pilasters. Thus in Poznań the motive of the hitherto used portico, as the expression of aspirations to power, was replaced by a loggia, which usually appeared when the architect wanted to emphasise the ‘mystery-temple’ aspect of the theatre. [4]

Whereas the approach of the architect to the elaboration of the facade differed from the solutions commonly used in typical Neoclassical theatre buildings, the layout of the auditorium remained more conventional. The auditorium was founded on the plan of a semicircle, with balconies and boxes. Only proscenium boxes were separated; there were no clear divisions between other boxes. However, it should be noted that, in comparison to the size of the audience, proscenium boxes were only a sort of ‘insignificant annex’ accented by the height and sculptured decoration. The places for the poorer audience were appointed on benches on the third balcony. On the ground floor there were places for the learning youth, where pupils of secondary schools crowded in. The theatre could hold 500 people altogether.

The programme of sculptured decorations in the proscenium differed from that usually applied in theatre buildings. It consisted not only of allegories of fine arts (attributes of music, poetry, painting, sculpture and architecture) and science (a book, a pen, a globe, an owl), but also industry (a toothed wheel, a distaff) and trade (the Mercury’s stick and an anchor). Thus the romantic conception of ‘the temple of art’ was completed with the programme of ‘organic work’.

[1] Zofia Ostrowska-Kębłowska 1982, Architektura i budownictwo w Poznaniu w latach 1780-1880, Poznań 1982, p. 440.

[2] Michiel Wagenaar, Stedebouw en burgerlijke vrijheid. De contrasterende carrrères van zes Europese hoofdsteden, Bussum 2001, pp. 54–59, 70–76; 84–86.

[3] Zofia Ostrowska-Kębłowska 1982, op. cit.s. 441.

[4] Ibid., p. 446.

Literature:

-

125 lat. Twierdza i teatr. Księga Jubileuszowa Teatru Polskiego w Poznaniu [1875-2000], ed. Krzysztof Kurek, Poznań 2000.

-

130 lat Teatru Polskiego w Poznaniu (1875 - 2005), ed. Marta Mielcarek, Joanna Nowak, Poznań 2005.

-

Beyond Everydayness. Theatre Arhcitecture in Central Europe, ed. Igor Kovacevic, National Theatre in Prague, Praga 2010.

-

Guderian-Czaplińska E., Albumy teatralne. Artyści poznańskich scen 1918-1939, Wydawnictwo Miejskie, Poznań 2003.

-

Guderian-Czaplińska E., Teatralna Arkadia. Poznańskie teatry dramatyczne 1918-1939, Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań 2004.

-

Ostrowska-Kębłowska Z., Architektura i budownictwo w Poznaniu w latach 1790-1880, Poznań 1982.

-

Ratajczak J., Życie teatralne Poznania. Część I-IV, Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, Poznań 1983-1985.

-

Teatr Polski w Poznaniu 1875-1975, ed. Andrzej Jakimiec, Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, Poznań1975.

-

Uśmiech Melpomeny. Teatry poznańskie, „Kronika Miasta Poznania”, 2000, No 3.

-

Wagenaar M., Stedebouw en burgerlijke vrijheid. De contrasterende carrrères van zes Europese hoofdsteden, Bussum 2001.

Avtor: Bożena Grzegorczyk

Bożena Grzegorczyk:

Dodatni podatki

Podatki še niso vneseni.

Dodaj podatke.